What are the chains on Marley’s feet a sign of?

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!

Marley’s lack of connection and ties seemed to have preserve him from the burden of relationships and heartbreak. He avoided facing himself, his past wounds and his humanity: his isolation and greed are a protection from human suffering.

Stave 1 tells us much more than we may think about modern loneliness and human longing for connection.

Here’s why I think this is the case.

Scrooge took his melancholy dinner in his usual melancholy tavern; and having read all the newspapers, and beguiled the rest of the evening with his banker’s-book, went home to bed. He lived in chambers which had once belonged to his deceased partner. They were a gloomy suite of rooms […]. Let it also be borne in mind that Scrooge had not bestowed one thought on Marley, since his last mention of his seven-years’ dead partner that afternoon. And then let any man explain to me, if he can, how it happened that Scrooge, having his key in the lock of the door, saw in the knocker, without its undergoing any intermediate process of change: not a knocker, but Marley’s face.

Marley’s face.

Jacob Marley, Ebenezer Scrooge’s former business partner, is a haunting, remorseful spirit in A Christmas Carol who embodies the consequences of a life driven by greed and selfishness. In life, Marley was much like Scrooge—cold, calculating, and indifferent to human connection or charity. In death, he is condemned to wander the earth with chains, symbolizing the weight of his past sins and material obsessions.

He comes to Scrooge to warn him of the same fate and, despite his own suffering, Marley displays a sense of care and urgency, along with his coldness and silence. He wants to protect Scrooge from a similar fate.

Marley doesn’t explicitly tell Scrooge why he has come, but I think the answer can be found in Dante, an author Dickens was most probably aware of and from which he most likely drew inspiration.

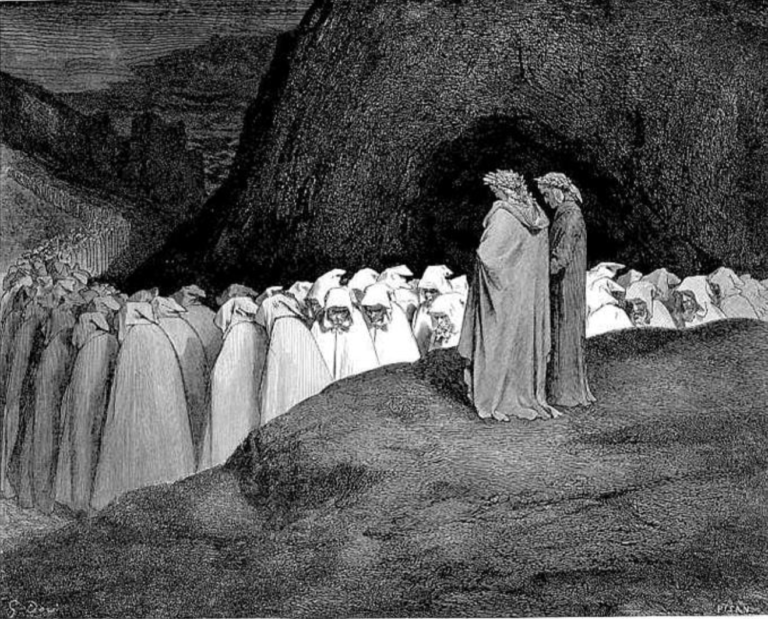

The pena di contrappasso (Italian for “punishment of retribution” or “counter-penalty”) is a key concept in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, particularly in Inferno, that refers to the idea that the punishment in Hell directly reflects, mirrors, or inverts the sin itself. In other words, each sinner’s punishment is uniquely tailored to their earthly sins in a way that symbolically fits the nature of those sins.

By way of example, let’s take Canto XXIII (Inferno), where Dante meets criminal hypocrites, who concealed the truth of their thoughts and actions behind a facade, masking their true intentions in life. In eternity, they are doomed to march forever, weighed down by dark cloaks lined with lead and so unbearably heavy that they can barely move. The cloaks are interestingly deceptively beautiful on the outside, but unbearably heavy within.

To cite another example, in Purgatorio, Dante encounters the proud on the first terrace of Mount Purgatory, punished by carrying massive stones on their backs. The weight forces them to bend low to the ground, bowing in humility, literally “lowering” themselves in repentance on their path. In life, they elevated themselves above others with pride and arrogance, but here they are brought low, humbled by the very weight they bear.

Where’s the parallel with Dickens, you may ask?

In Dickens’ description of Scrooge’s old partner, Marley’s soul is forever bound to walk in heavy chains forged from cashboxes, ledgers, and lockboxes.

“You are fettered,” said Scrooge, trembling. “Tell me why?”

“I wear the chain I forged in life,” replied the Ghost. “I made

it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on my own free will […]”.

“Seven years dead,” mused Scrooge. “And traveling all the time?”

“The whole time,” said the Ghost. “No rest, no peace. Incessant torture of remorse.”

The chains on Marley’s body are not a punishment for being immoral and a person with bad judgement towards others. Or at least, not merely.

Marley’s counter-punishment (pena di contrappasso) was his self-isolation.

“No man is an island”, as the poem goes, and Marley pays the consequences of his lack of meaningful relationships or connections in his afterlife.

I was moved to think about this parallel when a student of mine brought it to my attention in class last year. I thought that it also had a profound significance with our own self-inflicted isolation in the form of screens and mindless doom-scrolling that we are all accustomed in a post-pandemic age.

A study published in Frontiers in Human Dynamics found that during the COVID-19 pandemic, overall digital device usage increased by 5 hours, leading to screen times of up to 17.5 hours per day for heavy users. This surge in screen time, while facilitating virtual connections, often resulted in superficial interactions, contributing to a sense of isolation.

Technology provides us the perfect excuse sometimes to escape social interactions and statistically has been linked to increased feelings of loneliness.

We can’t escape the fact that we live in a digital age.

But just like Marley used his free will to self-isolate, we also are endowed with a choice to use technology to enrich our connections, instead of escaping them. Not all is lost, but as Dante and Dickens seem to suggest, it depends on our own free will.

What do you think?

If you want a tool to approach an in-depth understanding of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol Stave One, check out my Reading Guide and Discussion Questions Resources!

Have any thoughts or want to comment? Introduce yourself and let me know your thoughts below in the comment section. I would love to know your opinion.

If you want to read this amazing classic or gift it to someone this Christmas, you can purchase an edition on U.S. Amazon website:

- Hardcover: click here

- Kindle: click here

- Audiobook: click here

If you’re in the UK, purchase on UK Amazon store here.

These are affiliate links. If you purchase through them, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

[…] Why Read A Christmas Carol Stave 1: Chains, Marley and Modern Loneliness […]